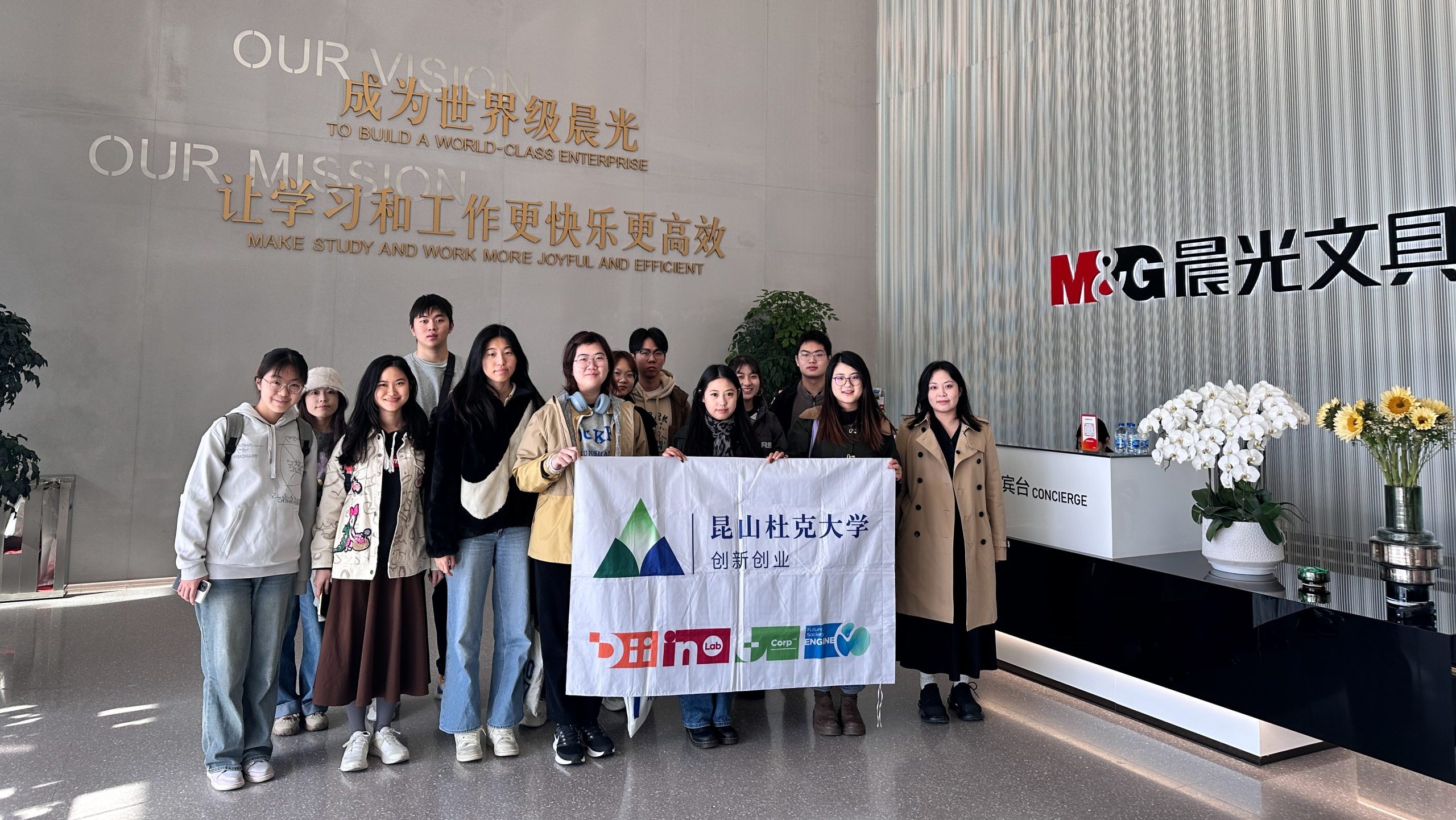

This early summer, I joined a field research project in Guanzhuang Town, Yuanling County, in collaboration with the public welfare organization PEER and DKU University-Corporation Innovation Lab (U-Corp lab). The project aims to explore the impact of generative artificial intelligence large language models on students’ creative writing and emotional expression in the county’s educational environment. Driven by an interest in county educational issues, I joined the on-site experimental phase of the project.

Building on the preliminary research by Huiqiao Yuan, Ai Zhou, and others, our team, with the support of Junyi, Harper, and our partner Ruo from PEER, embarked on a journey of observation, dialogue, experimentation, and reflection. We hope to establish not just a study on the application of artificial intelligence, but a shared perspective that transcends spatial boundaries, and a collaborative research endeavor. Through this note, we wish to share our story with a broader audience.

Part 1 [Finding the Problem Itself in the Field]

On the evening of our arrival in Guanzhuang, Huiqiao, Ai Zhou and I went to the rooftop of our hotel to watch the sky. From there, we could see the campus of Yuanling No. 6 Middle School. The dim light of dusk highlighted the neon signs, with the constant flow of large trucks on the highway, the layered mountains, the continuous rain of early summer in Hunan Province, and a student running around the playground over and over again.

We leaned on the railing, gazing at the distant campus, no one speaking, just watching, as if facing a blank answer sheet, with silence stretching into lines for writing answers.

The unknown and uncertainty were our biggest matters before the field research. Within the tight student schedule, we needed to communicate with the school authorities upon arrival to see if we could conduct experiments and then determine the experimental plan on the fly—our computers stored different versions of the experimental design.

In addition, the research question was our biggest concern. “Exploring the impact of the use of generative artificial intelligence large language models on students’ creative writing and emotional expression in the county context”—the subjects, context, and content were clear, but not specific.

Previously, Huiqiao and Ai Zhou’s group, under the guidance of Junyi and Harper, conducted in-depth research on numerous topics such as generative artificial intelligence, iFlytek Spark, prompt words, in-class compositions, and creative writing. Despite this, everyone was still not satisfied, as the target group for the research remained vague, and the combination of these topics with the county context was rigid and empty, leading to the internal question of “who is the subject of our research?” During the initial preventive talks with county students, Huiqiao fell into a long period of self-doubt, saying, “I’m not sure if we need to use AI. I talked with the students, and they are so smart. I don’t want AI to break these. I don’t know what we really want to ask.”

How to carry out a research topic? We look for areas that have not been noticed in the knowledge system, ask questions, and through data collection and analysis, we constantly try to get closer to the answer. But when we face specific people, what does this topic mean to them? Or more specifically, how do our questions, data, and answers resonate with their life context in this research experiment?

These doubts became our long-term concerns before the field research. But we knew that this was not something we, who were hundreds of kilometers away, could answer. Therefore, we put this question down lightly, leaving it to the real subjects of the research in the field—county students, to give their own answers. Openly, we are not looking for answers, but for questions—what we really want to ask and how they understand this question.

In the first two days at Yuanling No. 6 Middle School, we did not immediately start formal course experiments, but chatted and interviewed with students to know their daily lives, what they like, and what they yearn for. Just like the day before entering the school, Huiqiao, Ai Zhou, and I quietly watched the school in the clouds, silent and speechless. The silence stretched into infinite answers.

Under these questions, we named the experiment “What Story Do You Want to Tell.”

Part 2 [What Story Do You Want to Tell?]

On the recruitment poster, we bolded “you” and “story” with colored pens. We wanted students, as the main subjects of the research, to tell their own stories. Our task is to clearly see and understand—break wrong perceptions or supplement biased views.

When collecting creative writing materials, we were reminded that “creative writing is not easy” and were uncertain if students understood AI. But when we openly discussed the research topic with students, they frankly expressed their opinions.

Surprisingly, in our very random “catching” students to chat, many students had experiences in creative writing. One girl left a deep impression on me. She was a sophomore of high school, wearing thin glasses, with a medium-length ponytail. When chatting, she expressed her love for literature to me, took me to see the poems she wrote in her space, a little shy, with her eyelashes sparkling. When I mentioned AI and writing, the girl lowered her head, squatted on the ground, and said she didn’t like AI—even though her works were not perfect, they were her own voice.

Materials are different from inspiration. In the interview with this girl, we discussed this topic. “Inspiration is about telling one’s own story,” she told me. The desire to explore is growing. She shared her feelings after “first contact with feminism,” telling me about her new view of her once ashamed body, the change in literary aesthetics after the perspective shift, and the re-understanding of gender relations in her own family. These topics that go beyond the so-called “college entrance examination changes fate” narrative reflect their ability to understand and interpret the world. In their self-inclusive gaze and discussion of public issues, they re-understand their interaction with the surrounding environment.

The girl brought her micro-novel, saying it was inspired by a book about an anorexic girl. The girl told me, “I transformed my feelings for this book into a story I wrote, opening her up with my own perspective.” She also had her own story to tell, “I have been thinking about a story about a female general, and I like Liangyu Qin very much.”

A student showed me her fan fiction during a chat, hoping to get my advice. She proudly said, “This is the first time I have written a story with myself as the protagonist.” I remember habitually praising the article as interesting at the time, but she seemed unsatisfied, more regretful, until I gave specific suggestions. She was very happy, nodding thoughtfully while listening, and then left excitedly before the class bell.

What does writing and story mean? It seems that they are rarely considered a “necessity” to change fate, or just an extracurricular activity for students with extra energy, in high school where “enrollment rates” are still difficult, it seems very luxurious—“I can’t even do exercises in time.” But this underestimates the students, ignoring their energy to change the world. Writing is an expression, and the story is a declaration. What they lack is the opportunity and the occasion to speak and an evaluation system beyond the heavy stone called fate.

The girl mentioned an event that impressed me. She had an article about feminism selected in a class speech activity, but since she had already spoken before, she gave the manuscript to another student. “At that time, the girl’s voice was a bit small, and many people didn’t hear her clearly. It’s a pity.”

Voice, writing, and story are students’ actions to embed themselves in public society. I am willing to understand it as “participation” that transcends the self, while returning to the self, the sense of meaning is thus confirmed on the horizontal dimension. Aruo, a partner from PEER, said during the research, “Under sorting, competition, and elimination, there will always be people who fall behind, but through these activities, we hope to tell everyone—no matter how the grades are, remember to love yourself, remember to discover your own strengths and shining points.”

This also echoes the reason why Huiqiao and Ai Zhou chose creative writing as the research topic—we want to understand what students want to express. After the interview outline was basically answered, the semi-structured interview often ended up falling apart irrelevantly. On a damp evening after the rain, squatting in the wind and rain pavilion to chat about feminism, before the evening self-study, we listened to students share their understanding of various fan fiction and the understanding of “wife”—oh, and why they “abandoned” them (disliked them).

I remember once, the three of us were in the solemn studio, conducting focus group interviews with different groups of students at the same time. The outline had long been asked, but the students pulled us to talk about various strange stories they encountered in school, and before we knew it, we had talked for more than two hours. I still remember when the first interview ended, the student ran into the rain and said to me, “Thank you, sister, usually no one accompanies me to talk about these.” In fact, talking with them about these topics is very interesting in itself, fan fiction, little mushrooms, magic, and their abandoned ones—the vivid descriptions seem to make up for the colors I lacked in the past.

In this place full of grades, rankings, college entrance, and fate, the schedule and the stack of high books limit the flow and growth, but we can still write about the impulse of utopia in stories. Throughout the process and communication, no one discussed grades, and no one understood or defined others based on grades. Possibilities thus became diverse, and everyone freely expressed the story they wanted to write, whether it was a subtle perception of life or a longing for public ideals—a girl told me, “It may sound a bit ordinary, but my ideal is world peace. After seeing what happened in Palestine, I felt a connection with the knowledge in the books.” And this shining public spirit of knowledge, it really exists and needs to be illuminated, and this voice should be transmitted far beyond space.

Part 3 [We Cannot Turn a Blind Eye, We Must See]

These beautiful and vivid examples are not just stories told to comfort the distant place, they lead to deeper questions—about what we should do.

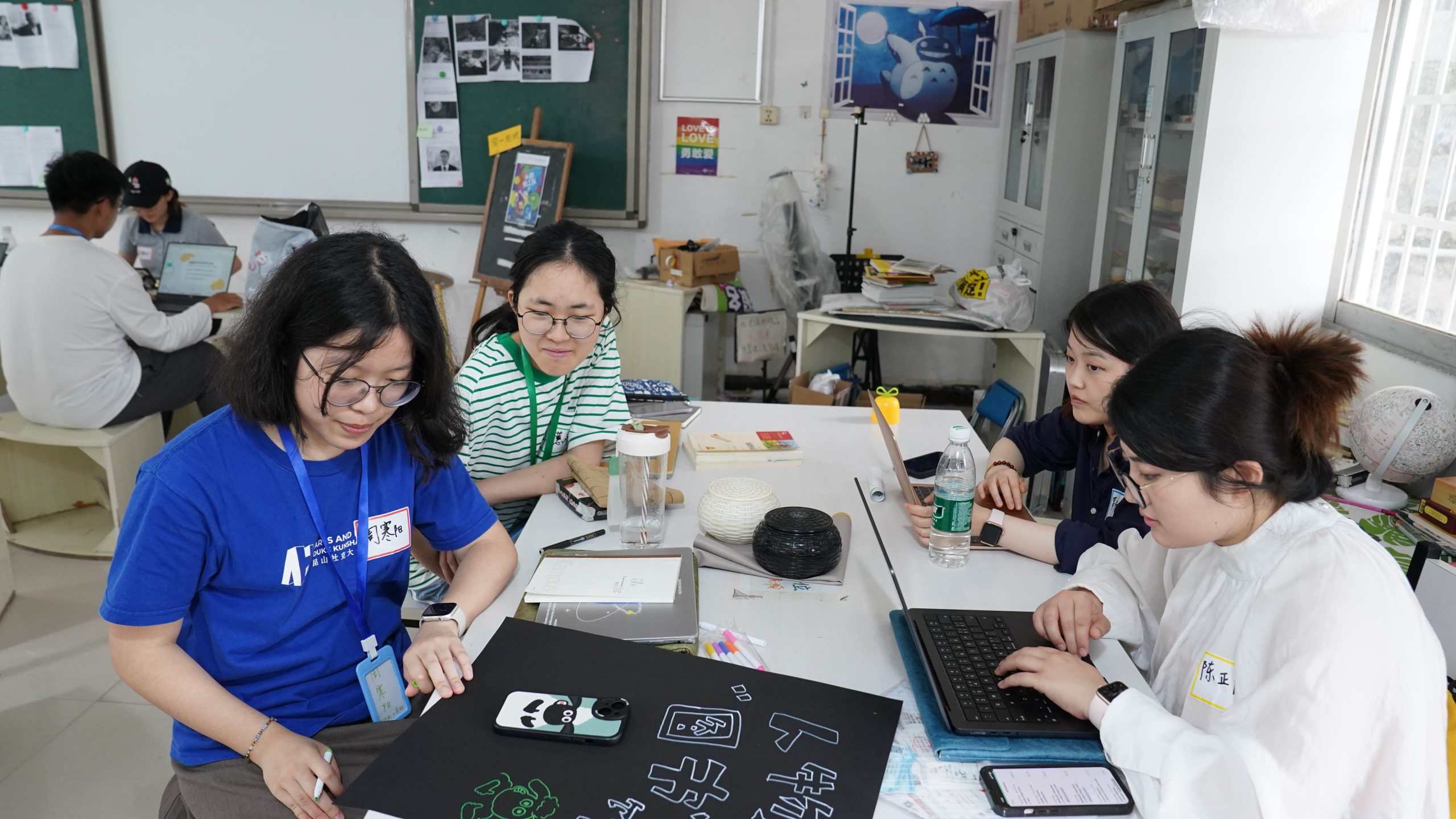

Under the theme of “What Story Do You Want to Tell,” we carried out a series of experiments with questioning as the main line, aiming to stimulate heuristic interaction in students’ creative writing through iFlytek Spark. I remember during the first experiment, I was in charge of the lecture part before the operation, and I was very nervous. During the practice, I went down to each student group to answer questions.

Due to the limited equipment, usually three or four people need to share a computer, which may result in only one or two students operating, while the other students just silently watch. After noticing this situation in one group, I discussed with them, “In the second half of the time, everyone will take turns to use it.” At that time, the students in the group who were not using the equipment waved their hands and said, “It’s okay, I don’t need to use it.” Frankly speaking, at that moment, I had a fleeting thought of “why not just give up,” but with the help of Junyi, we successfully let everyone take turns to use it. When I came back, I saw the girl who had been watching try to use it, with a smile in her eyes, very happy.

I felt a burst of warmth, and in a trance, I felt like the girl who waved her hand and said “I’m fine” was like me in the past—timid, but expecting to be noticed by the outside world. At that moment, I had a subtle feeling, as if I had traveled through time and space to embrace myself at that time.

A student asked me in class, “Sister, are you a college student? You don’t seem like a teacher.” I laughed, “Yes! Oh, it’s rare that no one said I’m old, my previous nickname has always been Granny Hanyang, haha.” In fact, I was joking at the time, but at the end, the girl ran over, pulled me aside, and stuffed a small piece of paper into my palm—“Sister, it’s for you!” Then she ran away quickly.

I opened my palm, and it was a piece of paper folded neatly, with the words:

“TO SISTER HANYANG ZHOU:

You are very beautiful, and you don’t look like a ‘grandma’, you’re so cute. Be happy every day ~ You are so gentle ^-^”

I was speechless for a moment, looking at these words, and it turned out that she was also embracing her current self.

In fact, no matter whether they are good at writing or expressing themselves, everyone has a story they secretly want to tell, and what we need to do is not something grand, but to try to see their desire to express, and gently embrace each other.

Later in a class, during the sharing session after practical training, there was a group of boys who were tanned, not paying attention during the lecture, but they gave a surprisingly good answer. After class, I talked with Huiqiao and Ai Zhou who assisted in that class and learned that they were actually very “unruly” at first, flipping through the computer, and not asking questions according to the prompts. “But they just lack some opportunities,” Huiqiao, who assisted this group of boys, told us at the time, “They seem to like Yu Hua very much,” and when Huiqiao used Yu Hua as an example, they started to ask questions according to the prompts, and later asked about writing thinking related to social phobia.

“I found that this group of sports brothers, who look a bit fierce, actually rely on each other’s protective relationship, just like the hidden topic they care about.” When they started to ask these topics related to themselves, everyone read the answers given by iFlytek Spark very seriously, and in the end, they gave me a very complete answer.

In our observation, whether they usually like writing or seem speechless, they actually have expectations and space for expression, and encouraging and telling them the value of their voice is a small but important thing we can do. For the hidden and silent words, we cannot turn a blind eye, but must clearly see, talk with them, and strive for freedom.

On June 7, 2024, the first day of the college entrance examination, which was also the last day of our experiment, we were surprised to find that this year’s Chinese college entrance examination composition topic was: “With the popularization of the Internet and the application of artificial intelligence, more and more problems can be quickly answered. So, will our questions become fewer and fewer?”

“Artificial Intelligence/Questions and Answers,” which fit the theme of the experimental course perfectly. We shared this topic in the group, making jokes about “hitting the topic.” But when we walked into the school at that moment, we suddenly felt a very deep worry—how could these students who took the same test paper respond to this question if they did not encounter sudden factors like us coming to do research experiments, and practiced asking questions to AI, and were unfamiliar with the keyboard?

This is not a pure vacuum, and they may feel the violence of power more directly than children in the city—naked and distorted power. But they trust goodwill, believe in sincerity and courage. I remember during an interview, a student described or experienced, or witnessed the darkness of the “adult world.” But they were holding a voice recorder in their hands, telling me the ugly events they saw one by one. At that time, I looked at that voice recorder, which was like a microphone in their hands. Although research ethics prevent me from disclosing this content in any sense, that scene and the trust they conveyed made me feel that they might want to use such a microphone to speak out and say something.

In this school surrounded by mountains, under the suppression and stuffiness we observed, the naive and innocent depiction of students is a fantasy of self-indulgence, and also an expectation that does not conform to the logic of growth, but I still want to praise loudly—their tenacity, courage, and expression of beauty and ugliness. Whether it is loud writing or quietly pulling a classmate over to whisper, it is a growing vine, striving to stretch outward.

Still, like the persistent question of “subjectivity,” the most critical thing is the students’ voices, their ability to write their own stories, their passion, and their desire to express. Beyond the narrative of grades, fate, and elimination, they can declare to the world, and they need to declare to themselves. A student once said in an interview, “In the countryside, the snow melts more slowly.”

Before leaving, the girl who participated in our experimental course found us and handed us two letters. The beginning of one letter read, “This is a suggestion letter…”

We read and laughed. The girl gave us a lot of constructive suggestions for our experimental course, and finally wrote—AI is very interesting, not what I thought before. But she hoped that she can tell the story of her own heart through writing.

I remember the confusion at the beginning about “what the problem itself is,” and the anxiety about subjectivity—through these close approaches, listening, telling, and dialogues, we let them talk a little more.

In this process, this is no longer a simple study on the application of artificial intelligence, nor is it just discussing county education. It is about expression, questioning, creation, and public participation, a collaborative research, a shared perspective that transcends spatial boundaries.

So let us keep asking:

You—what kind of story do you want to write?