Nestled against Tibetan Plateau to the west and bordered by Min River to the east, where mountains and waters embrace, a diverse and abundant array of flora and fauna thrives on this land known as Wolong. Here, ancient and vibrant folk song traditions are passed down from generation to generation. A student team from DKU’s Nature’s Echoes project ventured into Wolong Town, Wenchuan County, in Sichuan Province’s Aba Prefecture. During a two-week field study, they gathered materials and immersed themselves in the culture, and then they explored various narrative mediums to initiate the “Silent Land” art project. Ultimately, they presented Wolong’s unique folk song culture and field stories to the public through podcasts and exhibitions.

The interdisciplinary collaboration is a unique feature of this art project. Each team member brought different academic expertise to the project, providing integrated application of diverse perspectives and interdisciplinary skills in observation and expression. The project leader, Zhuoyuan Chen, an anthropology student, guided the team in strategic decision-making; Jingyang Lin, a digital designer studying computer science of computer and design, was responsible for graphic design and data processing. Hanyang Zhou, coming from a public policy background of the same major as Lin studied, acted as the podcast producer, responsible for planning the podcasts and analyzing data. Huiqiao Yuan, with an interest in global health, took charge of social media, accountable for the project’s creative ideas and publicity. Yuting Zeng, from the media arts major, worked as a curator to initiate creative works and analyses after the field research concluded. Boyan Zhang from computer science and Ruikang Wang from environmental science provided technical support and applied their expertise to realize artistic ideas practically, finally overcoming technical challenges.

For the team members heading to Wolong for field study, it was not only a new experience but also a daunting challenge outside of their comfort zone. Fieldwork emphasizes the recording of investigators’ personal experiences and a bottom-up approach, which entails extensive communication with the locals. For the four introvert members, they were more or less worried about their communication with unfamiliar respondents, fearing that it would be difficult for them to communicate with, empathize with or integrate into the group, thus affecting the comprehensiveness of their interviews and perceptions. Before going into the field, the girls had made thorough preparations, searched the information related to folk songs and media, learned audio and video collection techniques, studied the local natural and cultural context, and understood the spirit and methods of anthropological research… Upon their arrival in Wolong, they followed their original plan to interview local villagers, government officials, and individuals involved in cultural and environmental protection, collected audio of folk songs, sounds of the natural environment, and shot videos.

However, new challenges emerged. The residents of the three villages in Wolong Town quickly became aware of the arrival of these “outsiders”, but many of them, especially the middle-aged and the elderly, tended to be reserved in their communication, giving them generalized responses in the same way as they would a traveler. They encountered the first problem of the fieldwork: it is often difficult to go into the field and form a close connection with the site in a short time. They also needed to ponder how to introduce themselves as outsiders to gain understanding and acceptance, establish a sense of security and trust, and then start in-depth communications. For locals, their contact with outsiders is often limited to tourists and government officials. When faced with unfamiliar researchers with investigative purposes, the residents might need more time to understand their motives, and tend to utilize their previous experience with tourists to communicate with each other, resulting in one-sided information and perspectives gained by the researchers.

Another challenge came from the unknown nature of the field itself, as they summarized in the podcast, “It’s the steps of fieldwork that are the steps of discovery; it’s not exactly a proof phase.” Before starting the survey, based on the information provided by the project’s partner enterprise, Laotu, the team members learned that the local people and nature are closely connected, and took this as a presupposition for their data collection focus. However, during the actual investigation, they found that it was difficult to access a wide range of organisms in the village, making it unfeasible to carry out the anticipated biodiversity survey. Moreover, there were few elderly villagers who could sing folk songs, indicating a growing disconnect between nature and cultural expressions like folk music. “The academic research(themes) and the lives of ordinary people they faced upon truly entering the field were actually separated by a gap,” they said. Having been here for several days, it seemed that neither folk songs nor biodiversity data could be collected, and the reality of being so far from their expectations was confusing to the team.

A conversation with a noodle shop owner prompted them to begin reflecting on their communication approach. They initially intended to interview his wife that day, but as the owner sat eating noodles, he unexpectedly began to share information about his two university-educated sons and various local issues related to healthcare and education. No one volunteered a question, but his sharing was heartfelt and unreserved. “Sometimes it’s better to leave more space for them to say what they want to say. In this way, we can truly understand the problems the locals are facing and what they want to solve,” the team said.

With these feelings, they shifted their investigative focus from “verification” to exploration and experience. They continued to repeatedly visit the villagers to listen to their concerns. In addition to nature and wildlife, they photographed more labor tools and scenes of daily life, such as frosted Chinese cabbages and the tradition of slaughtering pigs for the New Year… Although their investigation seemed to deviate from the original theme day by day, they gradually integrated into the local social circle and the life through the villagers’ word of mouth. They were once invited to a grand wedding, and they watched villagers perform the Guozhuang Dance. They were also warmed by the fire with strangers who slaughtered the pigs, experiencing a close connection between different people in a typical rural society. As the process unfolded, more locals understood their intent and began introducing them to culturally relevant information and people who could sing folk songs. They met a young man familiar with folk songs and customs from a female innkeeper, and he introduced them to Grandpa Du at the market entrance, who was known for his pet phrase “can’t sing anymore” yet always continued to sing, and through a chance encounter with Grandpa Fan, they found Grandpa Youde Wang, from whom they recorded the longest piece of folk music “Making Rings”… Such seemingly scattered experiences and explorations in fact helped to collect information and left them with unique memories of their life there.

Leaving the field, they brought back a large amount of audio, photos, videos, and notes and the next step was to choose the right media to present them. After assessing technical feasibility and final results, the team eventually opted for podcasts and offline exhibitions to try to recreate the actual scenes of the field of Wolong through both visual and auditory perspectives, and they integrated their research reflections into these presentations. These various forms go beyond data collection and presentation. At the “Silent Land” exhibition, innovative multimedia designs such as a ceiling installation of glass jars and interactive jigsaw puzzles guided visitors to a deeper understanding and feeling of Wolong’s culture of folk music.

Particularly impressive was the “sound can” in the center of the exhibition hall. Visitors could hold a bottle close to their ears and hear a variety of sounds from Wolong’s fields and the project team that corresponded to the decorations inside the bottle, including bird calls, rustling winds, folk songs, and even the squeals of pigs. This interactive experience made visitors feel immersed in these scenes, thus creating a more tangible perception and identification with cultural and ecological conservation for them. The three podcast series titled “Participatory Observation” shared the team members’ field experiences and research ideas, and they invited leaders from InE(DKU Innovation and Entrepreneurship Initiative) and the cooperative enterprise Laotu to engage in discussions. Through vivid stories and reflections, the podcasts further deepened the audience’s sense of participation, and tried to enhance the understanding of field research methods, cross-cultural communication, and cultural heritage preservation between academia and the public.

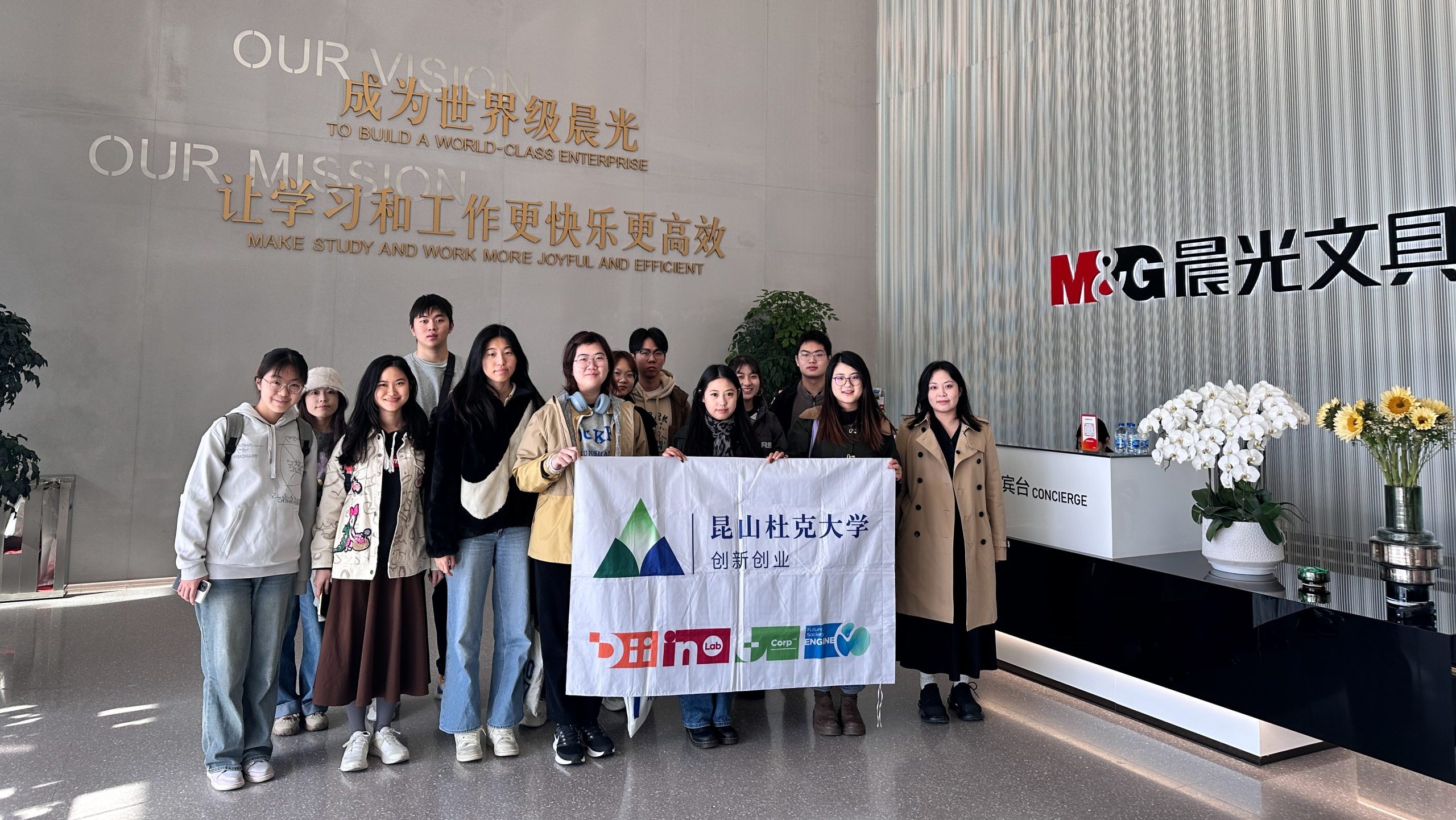

The project eventually evolved from the initial 2023 Fall University-Corporation Innovation Lab (U-Corp Lab) into a 2024 DKU Innovation Incubator Provincial Dachuang Project, and is now drawing to a close. A thousand kilometers to the west, the life of the residents of Wolong Town may still be working, resting, caring for their homestay business, neighborhood news, food and the vegetables. Folk songs may increasingly become a matter of hearsay and memory, yet the interactions it had with many people and the reflections it inspired, were preserved in re-creations. The history and culture behind it will be passed on in new ways. As project leader Zhuoyuan Chen stated in the final report, “What the researchers can do is perhaps not just to bring ancient folk songs back into modern life, but to keep their memories of these songs, so that when people wish to look back on the paths they’ve traveled, they will have songs to fall back on.”